Saturday 12/27

Congaree National Park

As we made our way south from a wonderful Christmas with family in northern Virginia, we decided to stretch our legs—and our spirits—at Congaree National Park. It felt like the perfect pause between holiday gatherings and the long road home to Florida.

At Congaree, we started on the upper section of the Boardwalk Loop, following its gentle rise through the quiet winter forest toward Weston Lake. The air was cool and still, and the towering Loblolly Pines along the route stood like an old friends welcoming us back. From there, we left the boardwalk and wandered a forest trail that carried us beneath a canopy so tall it felt like a vaulted ceiling of living wood. Eventually, the path led us back to the Visitor Center, where the warmth of the building contrasted beautifully with the wildness outside.

The lower boardwalk was closed for reconstruction—no surprise, since Congaree floods about ten times a year. When the river swells, the entire lower section disappears underwater. The new design will raise the walkway above historic flood levels, a thoughtful adaptation to a landscape that has always been shaped by water. Flooding isn’t an inconvenience here; it’s part of the park’s rhythm, the force that feeds the soil and sustains this extraordinary forest.

Even in winter, Congaree feels alive. We didn’t see fox squirrels this time, but knowing they roam these woods—bigger, bolder, and more colorful than their gray cousins—always makes us smile. And we couldn’t help thinking about the synchronous fireflies that light up the forest in summer, turning these same trees into a shimmering galaxy.

What makes Congaree truly unforgettable, though, is its scale. This 22,000‑acre park protects the largest remaining tract of old‑growth bottomland hardwood forest in the United States. It holds more record‑breaking trees than anywhere else in the country. Nowhere in eastern North America will you find a larger unbroken expanse of giants reaching 130 to over 160 feet into the sky. These broadleaf forests are among the tallest of their kind on Earth—taller than old‑growth stands in Japan, the Himalayas, and nearly all of Europe, and rivaling the great temperate forests of South America.

Thousands of Congaree’s giants still haven’t been formally measured. They simply stand, century after century, quietly keeping their own counsel.

Walking here together felt like stepping into a living time capsule—a place that endures, flood after flood, season after season. As we continued our journey back to Florida, we carried with us that sense of calm, that reminder of how rare and resilient this forest truly is.

Sesquicentennial State Park

From Congaree, we drove on to Sesquicentennial State Park—“Sesqui” to the locals—a place we’d heard about but never explored. It turned out to be one of those unexpected gems that make road trips feel like small adventures stitched together.

Our main goal was to see the FEMA bridge, a sleek 100‑foot aluminum span tucked deep in the woods. It was built after the devastating 2015 floods wiped out the old bridge over Jackson Creek, and knowing that history gave the hike a sense of purpose. But Sesqui had more stories waiting for us.

The moment we stepped out of the car, we realized we’d wandered into a living chapter of 1930s history. The entire 1,400‑acre park was shaped by the Civilian Conservation Corps, one of those New Deal programs that left a quiet but lasting legacy across the country. Here, the CCC built a man‑made lake, carved trails through the Sandhills, and engineered a beautiful stepped spillway that still sends water cascading from the lake into Jackson Creek. Standing there, watching the water tumble down the stonework, it was easy to imagine the young men who built it—many far from home, earning a dollar a day, shaping a park that would outlast them by generations.

We set off on the Sandhills Hiking Trail, winding through longleaf pines and sandy soil that felt worlds away from the flooded forests of Congaree. The trail linked seamlessly into the Jackson Creek Nature Trail, where the sound of running water grew louder with each step. From there, we followed the Loop Trail deeper into the woods until the aluminum bridge appeared—bright, modern, and almost futuristic against the backdrop of old forest and CCC craftsmanship.

Crossing it felt symbolic in a small way: a bridge built from necessity, resilience, and adaptation, standing in a park born from hard work during another difficult era. We paused in the middle, listening to Jackson Creek rushing below, grateful for the quiet and for the chance to share these places together on our slow journey back to Florida.

It was one of those stops that wasn’t planned as a highlight but became one anyway—the kind of discovery that makes the road feel a little wider and the trip feel a little richer.

Charleston

From Sesqui, we continued our drive toward Charleston, watching the landscape slowly shift from pine forests to marsh‑lined low country as we approached the coast. By the time we reached downtown, the late‑day light was settling beautifully over the historic district. We parked in the College of Charleston campus garage—an easy jumping‑off point—and set out on foot to explore this renown Southern city.

King Street greeted us with its usual energy. Even after the holidays, it felt festive, lined with high‑end boutiques, familiar national shops, and the kind of local storefronts that make you slow down and peek inside. Walking there felt like slipping into a blend of old Charleston charm and modern bustle, characteristics of old southern-style magic.

We followed King Street down to Market Street and wandered through the North, Central, and South Markets—rows of open‑air stalls that reminded us of the French Market back home in New Orleans. Sweetgrass basket weavers, local artisans, food vendors, and tourists all mingled under the long, breezy sheds. It’s one of those places where you can feel the layers of Charleston’s history in the air, from the city’s earliest trading days to the vibrant cultural crossroads it is now.

From the markets, we continued toward the waterfront until the grand white columns of the U.S. Customs House came into view, standing proudly above the harbor. Just beyond it was our destination for the evening: Fleet Landing, a waterfront bar and restaurant perched right over the water.

Instead of a full dinner, we decided to make a meal out of appetizers—something we love doing when a place has dishes too interesting to pass up. We shared the Fried Green Tomato Stack, layered with crab salad in a way that felt both indulgent and perfectly coastal. Then came the Stuffed Hush Puppies: oversized, golden, and filled with shrimp in a lemon meunière sauce, topped with crab and crispy sweet onion strips. These were unlike anything we’d ever had—rich, bright, and absolutely delicious. One of those dishes that makes you look at each other mid‑bite because you know you’ve stumbled onto something special.

It’s no wonder people say ithat the Stuffed Hush Puppies there are one of the “50 things you should do in Charleston.” Sitting there together, watching the harbor shift from daylight to evening while sharing plates that tasted like the Lowcountry itself, it felt like the perfect way to end the day before continuing our journey south.

Sunday, 12/28

Folly Beaches

We left Charleston that morning and drove through the lowlands toward Folly Beach, watching the marsh grasses ripple in the winter breeze. Folly always calls itself “the edge of America,” and standing on the pier, it really did feel that way. The county‑run fishing and sightseeing pier stretches an impressive 1,049 feet into the Atlantic—25 feet wide, 26 feet above the water, and long enough that the shoreline slowly fades behind you as you walk.

Out at the end, the ocean was alive. We watched porpoises glide just beyond the breakers, fish leaping in quick silver flashes, and fishermen lined along the railings with the easy patience of people who know the tides better than clocks. A few folks wandered the beach with metal detectors, sweeping the sand for lost treasures, while others stood at the railing with us capturing panoramic photos of the horizon. There was something peaceful about it — everyone doing their own thing, all drawn to the same stretch of ocean.

From there, we drove up Ashley Road to the county park overlooking the Morris Island Lighthouse. A leisurely half mile walk along a closed and graffiti decorated road led us to the remote beach. Once there, seeing the lighthouse standing alone in the water felt almost surreal. Built in 1876, automated in 1938, and decommissioned in 1962, the lighthouse now rises 161 feet above the waves—the tallest in South Carolina. Time and erosion have pushed the shoreline back, leaving the tower marooned offshore, a solitary sentinel still holding its place in history. We lingered there for a while, imagining the keepers who once climbed its spiral stairs.

We returned to the car and continued the opposite direction to the southern tip of Folly Island, passing neighborhoods with a mix of architectural styles—classic beach cottages, modern coastal homes, and everything in between. Each seemed to tell its own story about storms weathered and summers enjoyed.

Kiawah Island

From Folly, we drove through the quiet beauty of the low country toward Kiawah Island. Our destination was Kiawah Beachwalker Park—the only public access point on an island otherwise privately held. The park’s long boardwalk carried us over the dunes, carefully designed to protect the fragile habitat beneath. Out on the beach, the world felt wide and open.

Kiawah is known for its dune‑nesting birds—oystercatchers, plovers, terns—and even in winter, the shoreline felt like a sanctuary. But what fascinated us most was the thought of the Atlantic bottlenose dolphins that strand‑feed here. For fifty years, these dolphins have been working together to herd fish onto sandbars and mudbanks, launching themselves partly out of the water to feed. We didn’t catch them in the act this time, but just knowing this rare behavior happens here made the place feel even more special.

After soaking in the views, we continued our drive south toward Hilton Head, the late‑afternoon light settling softly over the marshes. It was one of those days that felt full but unhurried—each stop offering its own small wonder as we made our way closer to home.

Monday, 12/29

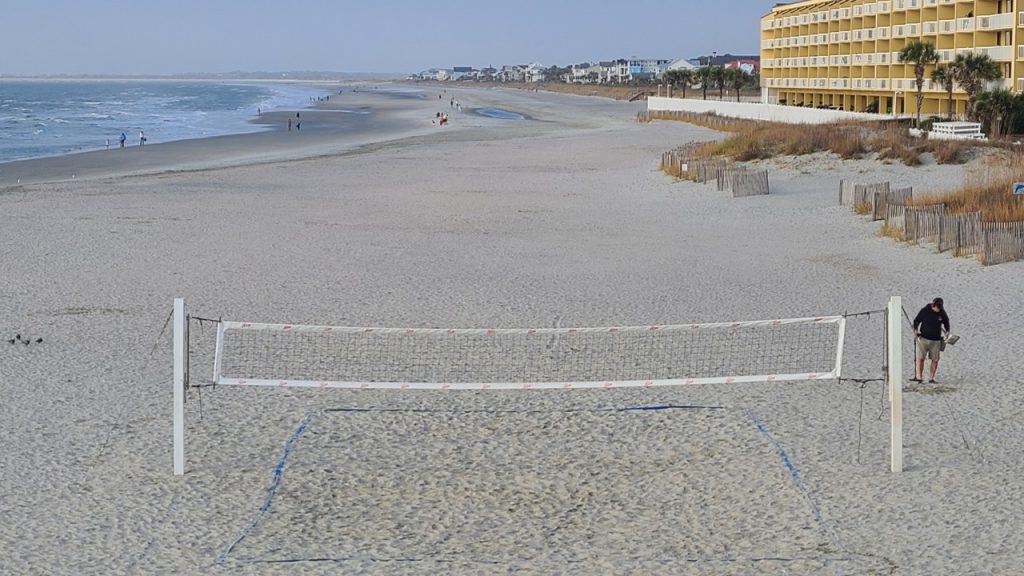

Hilton Head

The next morning, we woke to a cool, quiet Hilton Head morning and decided to spend the day exploring the island’s beaches and preserves before continuing home to Florida the next day. There’s something about Hilton Head in winter—calm, unhurried, and spacious—that makes it perfect for wandering.

Our first stop was Folly Field Beach Park, mid‑island on the Atlantic. Low tide had pulled the water far back, revealing a beach that felt impossibly wide and flat—one of the broadest stretches of sand on Hilton Head. Only a handful of people were out walking their dogs, leaving long footprints in the damp sand. The condos and apartments sat well behind the dunes, giving the shoreline a peaceful, open feel. It was the kind of beach where you breathe a little deeper without even realizing it.

Just a short drive away—barely three‑tenths of a mile—was Burkes Beach, tucked beside a large community park. To reach the sand, we crossed a small swampy area dotted with oysters and watched cormorants drying their wings on exposed branches. The beach itself was even quieter than Folly Field, known for its calm waters and wide, flat shoreline. No shells here, just smooth sand stretching toward the horizon. Again, the homes were set far back from the dunes, giving the whole place a sense of space and respect for the landscape.

From there we headed about five miles north to Fish Haul Beach, near Port Royal Sound. Low tide had transformed the shoreline into a vast expanse of mudflats and rocky patches where mussels clung in clusters. With waders, you could walk far out across the flats, and we watched locals setting up chairs and little play areas for their kids, turning the exposed landscape into an impromptu playground. It felt like a different world from the Atlantic-facing beaches—quieter, more elemental.

After exploring the shoreline, we drove inland to Pinckney Island National Wildlife Refuge, a place steeped in history. Commander Charles Pinckney—Revolutionary War officer and signer of the U.S. Constitution—once spent time here, and the island passed into his family’s hands in 1779. In the 1930s, it became a private game preserve, and in 1975, the family donated it to the United States as a wildlife refuge. Archaeological evidence shows people lived here over 10,000 years ago, long before any of its more recent chapters. Today, miles of trails wind through salt marsh, forest, and ponds, making it a haven for hikers, birders, and anyone who loves quiet places. We walked a bit of the trail system, feeling the weight of history in the stillness.

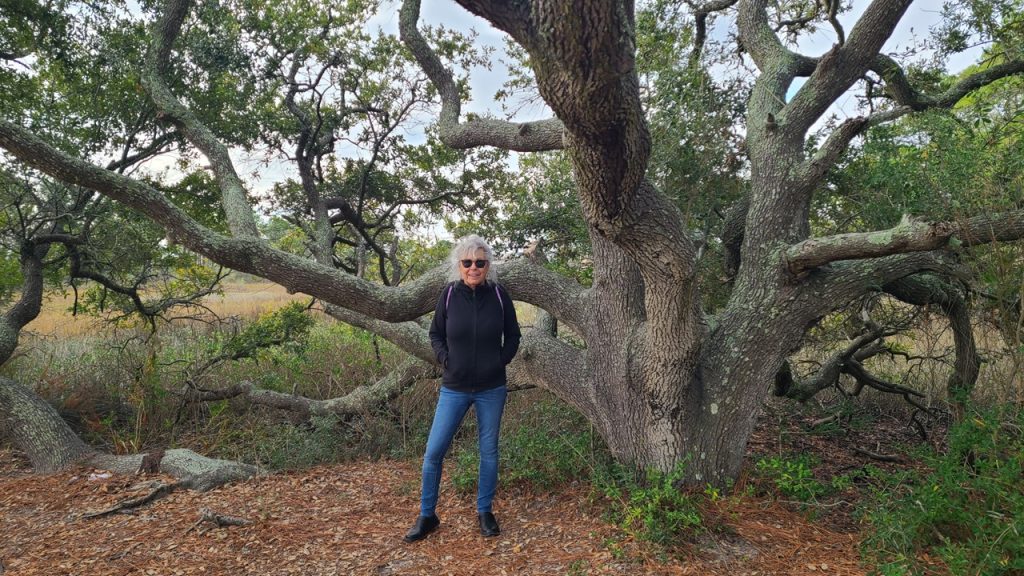

Our last stop of the day was the Sea Pines Forest Preserve, a remarkable 605‑acre sanctuary tucked inside the Sea Pines development. When the resort community was planned over 50 years ago, a quarter of the land was intentionally set aside as green space, preserving this already‑existing wildlife refuge. The land once grew rice, indigo, and cotton, and although Hurricane Matthew damaged thousands of trees in 2016, the restoration efforts have only strengthened the habitat and increased wildlife diversity. It remains the largest undeveloped tract on Hilton Head Island.

Driving and hiking under its canopy of pines and hardwoods felt like slipping into a pocket of tranquility hidden inside an otherwise bustling island. Birdwatchers dotted the trails, and signs warned of American alligators—quiet reminders that this is still wild land at heart. We wandered slowly, taking in the still ponds, the filtered light, and the sense of calm that settled over everything.

By the time we left the preserve, the sun was dipping low, casting long shadows across the road. It was the perfect final chapter to our Hilton Head day—a blend of beaches, history, wildlife, and quiet moments shared together before the last leg of our journey home to Florida the next morning.