Having left the Falkland Islands and passed Shag Rocks, we now travel on our Expedition Ship, The M.S. Fram, to The South Georgia Islands. South Georgia is considered part of the Antarctic environment and waters and air temperatures here are some of the coldest on earth. We prepare for our time there by attending a lecture by one of our Expedition Team’s Zoologist, Rob, who lived in South Georgia on Bird Island (one of the most northeastern islands) for 3-years from 1983-1986. He worked for FIDS, (Falklands Island Dependency Survey), now called “The British Antarctica Survey”, and he was flown there by the British Royal Navy via helicopter. While there, his responsibility was to study and count birds, including penguins, skuas, petrels and albatrosses. Skuas and Giant Petrels (“Northern” petrels have red tips on their beaks, and “Southern” petrels have green tips on their beaks), have done really well in the area. Also, fur seals on the island have also rebounded from the 19th Century Seal hunters where there were only 10 remaining fur seals counted at the beginning of the 20th Century, and today the local population is over 3 million. Rob noted that when he was there with a Team, the only time any of them got sick was when visitors arrived. His Team was consisted of 8 people in the summer and only 3 of them stayed the winter. Their base subsisted on British Navy Stores, including a good bit of alcohol. Bird island is still the smallest base of British Antarctica Survey, and Rob has never before returned to the South Georgia Islands and is excited to be heading that direction.

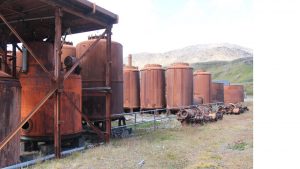

South Georgia has the most mountains of all southern islands and was populated in the late 1800’s until the 1960’s with an abundance of Whaling Stations, (mostly Norwegians, Irish and Argentinians). With the collapse of the Whaling Industry, most of these Whaling Stations are now abandoned and deserted. Today, they consist of rusting iron works, grounded and sunken ships, and asbestos contamination. The only inhabitants of many of these stations are the old fur seals that have taken them over. Our first stop must be the capitol town of Grytviken, an old whaling station that was not deserted until late 1990’s, and so its buildings are in better shape. Here, there is a small office and research center that manages the islands. We will need to clear a bio-inspection here and the ship inspected before we will be allowed to land anywhere in the islands.

At most of our landings, we will only expect to see penguins and female fur seals and their pups as the males have already departed shore and gone back to sea. Fur seals can be aggressive and move quickly, and we are instructed to “make ourselves big” if charged by one. Male fur seals can weigh up to 150kg each. We will also see male elephant seals which will weigh-in at ~3-tons and be around 9-feet long, however, they move relatively slowly and can be easily avoided. In general, all the areas near the shore, including the yards, will be full of seals. In addition to fur seals, there are Leopard seals which eat penguins, are aggressive, and have nasty teeth. However, they are usually only around ice sheets, and we will likely not see them until we reach Antarctica. What we will see are different types of penguins – Rock-hoppers, King, Gentoo, Chinstrap and Macaroni. We will also see a great variety of other birds, including: The Storm Petrel of which over 1.5 million breeding pairs are located here; the Cape Petrel with its pretty, lacy feathers and its making sounds like a chicken; the scavenging and predatory Skua bird (which is often seen in penguins colony trying to eat their chicks); the Sheath-bill petrel which likes to steal food from baby penguins; and the Pivot (only 3 thousand pairs) which is the only songbird in the Antarctic region.

There are no native shrubs or trees on South Georgia, only the windbreaks that were imported earlier by the whalers. In addition, the Whalers brought reindeer, cows, horses, and, unfortunately, the European brown rat (accidentally introduced over 2-century ago). The brown rat was particularly a serious problem, since the massive bird population nests on the ground, and the rats devastated the eggs and chicks. In 2010, a program was instituted to eradicate brown rats from South Georgia, and rat poison was carefully distributed by hand and by helicopter to all the infested areas. The program continued through 2015 and included rat-sniffing dogs and verification baits. Since 2018, the islands have been declared completely rat-free and bird colonies are on the increase. The highly successful program cost only ~$15M USD and over 67 nations contributed to its funding. In the future, all ships that come to the islands will be inspected by dogs at the Falklands port prior to being able to come to South Georgia. In addition, all reindeer were eradicated from the islands in 2012. Today, the sealing industry does not operate here, and seal populations have exploded to the point that they are starting to erode some beaches.

We will also hope to see the declining Wandering Albatross – the largest seabird with a 3-meters wing span and 40 inches in height. These birds only breed every other year, and care for their young for ~11-months before the chick leaves the nest. They require daily meals of over one kilogram of fish or krill to survive, and their numbers are slowly decreasing, although it is not clear why.

Friday morning, February 15th, we get up early to watch our ship pull into Cumberland Bay in front of Grytviken. When we arrive, the South Georgia bio-team was waiting on shore for us to bring them to our boat to commence bio-checks and immediately come aboard. The 3 Government observers aboard who come aboard bring a speaker from the South Georgia Heritage Trust, Sarah, who reviews the history of the island and the guidelines to protect the animals. As the ship is being inspected, Sarah gives us a briefing instructing us to leave no evidence of our visit, to keep our voices low on the island. She also reminds us that the animals have priority/right-of-way, and that we need to move slowly when near them. She informs us about the invasive species eradication programs and relates that the glacier between the center section and the north section of the island is retreating at about 2-meters a day. She also recommends a book – “Reclaiming South Georgia “- to those who are interested in learning more. Currently, Grytviken is hosting whale biologists who are studying Right Whales which breed off the coast of South America, but whose calves are beaching themselves and researchers don’t know why.

Check out the website: www.happywhale.com

Currently, 2 humpback whales in South Georgia are outfitted with trackers and are at the southern end of the island. The Trust is also researching Grey-headed albatrosses, which have declined 43% in 11 years and are unsure why, (they suspect illegal long-line fishing by-catch). The Trust has a program for individuals to help by participating in their “Protect a Hectare” (2.4 acres) Project/Sponsorship – see:

Facebook/southgeorgiaheritagetrust

Their goal is to become the nesting site of a hundred million more birds!

After a detailed inspection of every individuals boots and gear with headlamps and magnifying lenses, we are allowed to go ashore. The “hikers” were taken ashore first followed by the rest of us. They are doing the Maiviken hike starting from Grytviken and climbing to the Shackleton plateau 200 meters up high. The hike is for experienced hikers as it is steeper and longer than any other hikes we have done, and it will take 2-3 hours, which will limit their time in town. We opted to spend our time in town instead.

We spend the next 2+ hours exploring the area. We start with the cemetery where Shackleton is buried and where his headstone immortalizes his contribution to the region. From here, we pick our way among the fur seals and king penguins towards the old whaling village. All around us, there are numerous baby seals frolicking at the shore line, calling for their moms, and curiously checking us out. A few large male elephant seals were around lazing in the sun. We were able to walk the area of the old whaling factory, as this site was cleaned-up and all asbestos was removed. We finally arrive at the old Managers Villa, which is now the Island’s museum. The museum has lots of South Georgia and Whaling artifacts and tells the story of the Whaling Camps and Industry quite well. They even have a Post Office (only open in the summer) where we purchased postcards and mailed them back to the USA. The town’s name “Grytviken” means “pot” and was based upon the fact that the first settlers found old pots left behind by transient whalers there. The Grytviken Whaling Factory was run from 1904 until 1965, when it was closed for good. Along the coast, beyond the original camp is the research station at Edward Point, run by the British Antarctica Survey (BAS). Besides the Museum and the Post Office, Grytviken also has a gift shop and huge fuel tanks for petrol to run the village. They obtain their stores regularly from the BAS base. There is also the original one-room church which the whaling station sponsored to keep the men “in-line” (unsuccessfully). It was where Shackleton’s funeral was held, and last month there was even a wedding held there. The local Gallery contains South Georgian art and holds a replica of the boat Shackleton took from Elephant Island to South Georgia after his Antarctica ship was crushed by the ice. We also took a 20-minute guided tour around the camp with an intern stationed there for the summer. All the fuel containers and whaling equipment for harvesting meat and oil and blubber are still there, as well as some wrecks of the “whale-chaser” ships in the main harbor. We were then back aboard the Fram by about 12:15pm. Soon thereafter, the ship lifts anchor and we left Grytviken and head back southeast to St. Andrews Bay. This bay is home to over 200,000 King penguin-pairs, and only 100 people may be ashore at any one time. This will require us to stagger our visits in order to allow all some time on the island. The weather has been 38-40 degrees, but the lower winds and full sun will hopefully make for a very pleasant visit.

We arrive at St. Andrews Bay at about 3:30pm only to be greeted by dark clouds, strong winds and cold temperatures. The wind and swell were too high to safely launch and land the zodiacs, but we could see king penguins in the distance all over the beach and moraine. We could also see the Heaney Glacier and Cook Glacier coming down into the bay. After maneuvering the ship several times to try to accommodate the swell and block the wind, the Captain cancels the landing and we set sail, instead, for Royal Bay located down the coast.

On the way to Royal Bay, we came across a lone humpback whale blowing, breeching, and slapping the water with its fins, making splashes and putting on a show that all of the previously disappointed passengers thoroughly enjoyed. The Captain followed the whale for ~40 minutes before continuing our journey to Royal Bay. In Royal Bay, we saw the huge Ross Glacier and the Hindle Glacier. On this Bay, in the 1860’s, was once of the first settlements on South Georgia Islands. However, the winds were again too high to do more that cruise the ship into the bay for a look-see, making our way around some icebergs in position to view the glaciers. We could also see a large king penguin colony on the beach on the left side of the bay. But, because we cannot land, we leave this bay as well, reverse course, and head back northwest towards the opposite end of the island to attempt a landing the next day.

That night was Italian Dinner Buffet and while we ate dinner, we saw fur seals and small Humboldt penguins swimming in the water next to the ship. We also were informed that the ship received a rare perfect-score of 100% from the Island’s inspectors on our ship’s bio-security checks today!! Tonight, in the ship’s panoramic lounge, the Captain arrives with 10 others of the crew (sailors and engineers) to hold a knot tying demonstration, with each crew member coming to a guest’s table with ropes, lines, pictures and instructions. It was a great way to meet crew members that we don’t usually get to see.

During the night, the ship makes its way to Prion Island in the Bay of Isles, and we awake on Saturday morning to see penguins diving & swimming outside of our window. While checking the view on deck, we see huge Wandering Albatrosses circle overhead.

At 7am, the Exhibition Crew makes ready to go ashore as the weather is perfect for a landing. Prion Island is a very small island and was named after the Prion Bird that nests under the Tussock grass on the island. We are not likely to see any Prions during the day, as they emerge and hunt principally at night. This island is a “Specially Protected Area” by the South Georgian Government and has always been rat free. It was discovered in 1912-13 by Robert Murphy, an American naturalist, and is also the home to breeding Wandering Albatrosses. The Naturalists built a controversial raised boardwalk from the beach to the top of a small hill to ensure that nests could be counted without creating any further damage or impact to the environment. The boardwalk, with 2 viewing stations, was built in February-March 2008 and it provided a convenient path for us (and the local fur seal population), to see several nests with the albatrosses sitting and guarding their eggs. The island is also a breeding area for the South Georgia pipits and the burrowing petrels. Since Prion Island has this special status, only 50 people are allowed on the island, (including Expedition Crew, guides and safety personnel), at any one time. Therefore, the ship will spend the whole day here so that everyone gets a good chance to visit.

On arrival we were greeted by seals, gentoo penguins and one lone King penguin. It turns out that there are very many fur seals here, including a great number of seal pups, many moms and even a few dads. As we walked the boardwalk, we found seals in every little nook and cranny of the grasses beside us. We even saw a seal pup suckling from its mom right next to the boardwalk. The higher we climbed, the more birds were found. Two skuas landed right next to us chasing off a third and claiming his area and meal! At the summit viewing station, we saw a number of huge albatross’ nests with Wandering Albatrosses sitting on them and totally ignoring us. There were several Wandering Albatrosses flying overhead and tending their nest, as well. And many a seal pup tried to walk with us on the boardwalk. As we returned to the beach to get on the zodiac, a large male fur seal decided to rest in the middle of the beach path, probably weighing in at over 600 pounds! This was a unique island and one the ship doesn’t get to stop at very often, as many of the exhibition crew had never been here before. While we were on the island, several people took the double kayaks out for a ride, since the winds were low, and the surf was calm. Since Prion Island is in the Bay of Isles, the protected area there was perfect for kayaking.

After the Prion landings were complete, the ship set sail to Salisbury Plain, which is also in the Bay of Isles. Here we saw a very large king penguin colony – the 2nd largest colony in the South Georgia Islands, after the St. Andrews colony. The day was getting late so we didn’t have time for a landing here, but, since the waves and wind were calm, we did put the zodiacs in the water and took cruises up and down the beach. There were king penguins everywhere, with a few seals mixed in. The beach almost had an orange-yellow hue due to their coloring and density there. The penguins also played in the water next to the zodiacs and were climbing and diving off the ship’s bow bulb. Once back on board, there was a Mexican buffet dinner followed by a briefing on the next day’s potential landings – Fortuna Bay and Stromness Bay. By night, it is snowing wet big flakes and we gather in the panorama lounge for an Officer’s Fashion Show, featuring the ship’s Officers and Expedition Crew modeling clothing from the gift shop. The DJ is Jose, our cabin housekeeper. The officers/crew modeled t-shirts, sweaters, coats, and accessories. But the best display was a guide dressed up in knickers and a coat from the early 1900’s. The finale stole the show as it included 2-crew dressed in white terry cloth robes wearing 1920’s one-piece striped swimwear! The lounge was packed with passengers for this event and it was the best attended night-time activity, yet.

Afterwards the fashion show, we went into the hot tub outside on deck-7 and watched the snow fall around us.

On Sunday, when we awoke, we were surrounded by the snowy white peaks of Fortuna Bay and we see king penguins and seals playing in the water outside our window – it is 38 degrees outside. We arrived in Fortuna Bay in the middle of the night and stayed here since it was well-protected and calm. Fortuna Bay was named for one of the first whaling ships that operated in the area. The inaptly named Fortuna ran aground at Hope Point in 1916, as her helmsman was reading a letter from home. This bay is home to both king & gentoo penguins, fur seals, elephant seals and many species of birds, including the albatrosses and the giant petrels. The king penguins prefer to nest at long open beaches with large swells. The colony of penguins here at Whistle Cove in Fortuna Bay is one of the most easily assessable in South Georgia Islands.

At 7:30am, the Expedition Crew went ashore and began setting up the landing. Soon, we took the zodiacs to shore and were greeted by many more seals and king penguins. The king penguins were everywhere and they not shy – they walked right up to us and were curious about the seldom seen humans. We began our walk left down the beach toward the valley, and there were penguins all along the beach. We finally crossed a small river and then the area we were in was dominated by thousands of fur seals, some of which we needed to hold off from their charges. We continue our walk until we reach to a hill, and from on top the hill, all one can see is fields full of king and gentoo penguins – over ~10,000 pairs – squawking and tending their nests. After many pictures, we walk back down to the beach and the penguins begin to follow us. Eventually, we return to the ship, but on the way back, we find a group of penguins again sitting on the bulb at the front of the ship, creating their own little playground. They were using the bulb as a platform, diving into the water and then climbing out and diving again – they were so cute. The penguins have been playing in the waters around the ship the whole time we have been here, (they can swim at 12 mph). The whole excursion was done with sleet and snow falling and a combination of clouds. and then sun, and then clouds again.

After the excursion, we eat an early buffet lunch in anticipation of hiking part the Shackleton Trail in the afternoon. When Shackleton reached the South Georgia Islands with their lifeboat from Elephant Island, he and two others hiked across the islands to Fortuna Bay, and then to the Whaling Station at Stromness Bay. However, we soon learn that due to very low visibility on the mountain pass, the hike was canceled. However, we are still going to sail around to Stromness Bay and go ashore and hike part of the trail to Shackleton’s Waterfall and back.

When sailing into Stromness Bay, on our right is Leith Harbor, the site of one of the largest old whaling stations in the islands. We can also see the rusting site of the old Husvik whaling station that also used this bay. It was here at the Husvik station that the entire whaling staff volunteered to rescue Shackleton’s 22 men who were still stranded on Elephant Island. However, the men of Husvik would not be able to get through the ice flows surrounding Elephant Island and that first rescue attempt failed. It would take 4 attempts in total, and over 4 more months for Shackleton to finally reach his men and effect their rescue. When we go ashore at Stromness, it is a wet landing on the beach, and we are greeted by many elephant and fur seals. The hike to the back of the valley takes a solid hour, across glacial streams and braided channels of rocks and ice. Once we arrive at the back of the valley, we get to see Shackleton’s waterfall, the largest waterfall on the island, and the point at which he descended from the mountain pass to get to the Stromness Whaling Station. As we walked to the waterfall, we come across some colonies of Gentoo penguins in a small side valley – they have walked over a mile across the grass and rocks to get here. Stromness Whaling Station is still there, but it is now abandoned, and because the site has not been cleaned-up, we are required to stay 200 meters away from its contaminated, decrepit structures. Stromness Whaling Station was active from 1907-1961, but no one lives or stays here now. The weather for the afternoon’s hike has been overcast with a mixture of snow, sleet and intermittent rain, and the katabatic winds, (30-60 mph gusts), from the mountain glaciers come and go.

On our return, we divert our route and head over to the back side of the old whaling station where we could hear elephant seals trumpeting in the distance and where we could get a better view of the relics. The ground here was solid muck with your feet sinking on every step. After a plodding 20-minute walk and a brief sighting and pictures, we reverse our route and head back to the ship. While waiting to board the zodiac, the king penguins and fur seals surrounded us. There were a huge number of young baby seals here, and they are very curious about us and what we are doing. As we returned to the ship, a rescue-lifeboat was being lowered into the bay as part of normal seafaring rules and safety checks. The rescue-lifeboats need to be lowered every 14-days while at sea, and the engines run and checked. That night, after an Asian buffet, we went to spa tubs on deck, and found a small Diving Petrel bird huddled in the corner next to the tub. We notified the Expedition Crew and they picked it up, kept it warm for the night and released it into the wind in the morning.

It is Monday morning, February 18th, and today will be our last day in the South Georgia Islands. The weather expected for today is not good, and will include snow, rain, sleet, and high wind and swells. In the morning, we head to explore Gold Harbor. It is called Gold Harbor because surrounding mountain peaks are so high and angular that, with sun on them, they look yellow and give a “golden glow” to the bay. When Captain Cook arrived here, he was disappointed to have discovered that it was not the Southern Continent that he had hoped to find. This area is a breeding ground for king and gentoo penguins as well as light-mantled albatrosses. As the ship enters the bay, we can see king and gentoo penguins on the beach. However, one can smell them before you even see them! Pictures of the glacier that comes into this bay from 2004 clearly shows its rapid retreat of many meters per year. After the ship circles a number of times, the Captain determines that the katabatic winds make it impossible to launch zodiacs or make a landing here. Therefore, we decide to head down the coast to Cooper Bay & Cooper Island.

Cooper Island was discovered by British explore James Cook in 1775, however, the island and facing bay are named for Lieutenant Robert Cooper, an officer aboard the HMS Resolution. Cooper Bay has large number of sea birds, including snow petrels, Antarctic prions, and over 12,000-pairs of black-brown albatrosses. On the exposed outcrops here, we see chinstrap and macaroni penguins (~20,000). Both types are in the water around the ship as well as on the shores. It is so windy here that it is difficult to even hold the camera still for a picture. After holding the ship’s position for ~20-minutes for pictures, we head through the narrow neck of water between the island and the mainland, nimbly passing close to huge rocks on either side. In front of us, are the South Asian Mountain Range with Ferguson Peak, Douglas Crack, and a number of mountains that are over 2000 feet high.

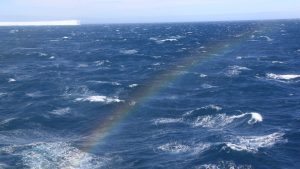

After passing Cooper Island, we head for the Drygalski Fjord. It is the largest and truest fjord on the island, with several very large glaciers located at its end. The fjord is named for Erich Dagobert von Drygalski, a professor of geography and geophysicists at the University of Berlin. Drygalski led the German Polar Expedition in 1901-1903 and helped describe the area. We cruised all the way to the end of the fjord for pictures. Since the mountains are so tall on both sides of the ship, it is very quiet, but also very windy. We have not seen another ship in these areas and the Captain works hard to keep the ship positioned in the center of the fjord. Eventually, he pivots the ship expertly, and we leave the fjord slowly. Once we exit the fjord, in the distance, we can see a massive, tabular shelf iceberg from Antarctica that has broken off the ice-shelf. As we draw closer, we can estimate that it measures ~1.9 kilometers in length!

Since the winds have been uncooperative today, the Captain has announced that we will set sail immediately for Elephant Island and Antarctica to the south, and whatever new adventures await us there. Consequently, it was a quiet afternoon on ship with a Spanish Buffet dinner. However, by the evening, the waves had grown to nearly 50 ft and seasickness has driven a large number of passengers to their cabins.

Today is Tuesday, February 19th, and we will spend the next 3-days battling winds and swells to arrive in Antarctica. Upon awakening, the waves and swells are less than the brutal conditions of the previous night, and the breakfast buffet is reasonably well-attended. Since the entire day will be at sea, lectures are offered to help everyone pass the time on-board.

The first of these was a lecture by our Russian Expedition Team Member, Katya, titled, “Destination Antarctica: Life and Work in Antarctica”. Katya is a marine biologist with ten-years of experience working in Antarctica. She showed us a beautiful sunlight picture of Paradise Harbor/Bay taken from the Almirante Brown Station where a good percentage of the time it is sunny. Antarctica is the windiest and driest place on earth, however, there are ~70 permanent research station scattered throughout the continent representing 29 countries. Katya has worked on a Russian base, a German base and a British base. As a student, she went to King George island in the Southern Shetland Islands. King George Island is a glacier-covered island except for a small peninsula on the southern end. There are 5 different bases and an airport in this area, that allows more reasonable access and cooperation. Although Katya is Russian, she splits her time between Russia and Washington D.C. The Soviet Union used to have 12 bases but, after the cold-war ended, closed 5 of them, and now has only 7, 2 are temporary bases that hold weather stations and other electronics, and that are only visited temporarily. Base Bellinghausen is jointly staffed with Russian and Chilean personnel and opened in 1968. The Russian side of the base can hold 50 personnel but only 10 in the winter, and no women are allowed to stay over the winter. They have a library, an Orthodox church (wooden – which means they had to get special permission to bring in specially treated wood to construct the church), a hospital, garages, labs, workshops, and housing. The base also has a runway and a helicopter hanger. Some of the research done is the study of Antarctic “hair grass” which is an invasive species. The researchers map the area covered by the grasses by GPS and have continued to monitor whether it is spreading or dying. They also study Adelie, Gentoo, and Chinstrap penguins, especially the breeding pairs. Although these penguins are everywhere across Antarctica, their local population changes are of significant interest to scientists. Penguins are very curious and will readily approach humans. There studies are finding that Gentoo penguins are on the increase, but the Adelie and Chinstrap penguins have been decreasing over the past 20-years. This long-term research has also noted that the Weddell seals and the south-polar skuas are also declining in this area. In addition to the wildlife counting, the research personnel also hunt and record fossils. The fossils that are found on this island show evidence of plants, animals, and wood that clarify the geologic history of the island. Also, since the base has a helicopter, they have participated in a variety of rescue operations. Although the Russians share the base with the Chileans, they each have their own area and set of buildings. The Russians have green-colored buildings in the front of the base, and the Chileans have multi-colored buildings at the back of the base. The Chileans personnel are mostly military-based people, who have 2-to-3-year commitments, and therefore they are allowed to have their families with them. Altogether, the Chilean base has about 100-people of which 25 are children (the first baby born in Antarctica was to a Chilean family at this base). They also have a school, grocery and a bank. They even offer a tourist program – “One Day in Antarctica”. There are flights to the base from Punto Arenas 2-3 times a week. Also, nearby, is the Chinese base, which has 50 people in the summer, but usually only 10 people in the winter. However, the Chinese have really good laboratories, which they are willing to share. All of the bases are open to all people on Antarctica at any time. Each base in Antarctica keeps its own time zone – usually tied to their home country. For example, the Chinese operate their base on a Chinese time zone, where the Chileans operate theirs on Chilean time zone. Although this is convenient for communications to home countries, it does make inter-base communications and visits complicated. All bases are also a minimum of 25-kilometers from the ice edge and, if a ship comes in, it pulls up directly next to the ice-shelf. Katja also worked on an ice breaker ship for nearly 3-months, doing research on the Southern Ocean and Antarctic Krill. They too had a helicopter, which they used to count whales and spot krill gatherings. She also spent time at the German base, Neumayer, which was established in 2009 and is built on innovative hydraulic stilts, as the ice is always moving beneath it. Katya also worked on the British base, Rothera, which opened in 2008 to study ice rocks and the Antarctic water. The base is unique in that it has hills around the camp, and the personnel located there are able to ski and snowboard. However, since there is no lift system, they use snowmobiles to get to themselves to the top of the hill.

As the day went on the swells/waves got bigger and bigger. Dinner was minimally attended, and all evening sessions and lectures were canceled due to the waves. The outside decks were roped off, and everything was battened-down for the rough seas. That night, everyone went to bed early, as the waves reached the top deck of the boat 20-30 meters high, and wind was 50-70mph.

On Wednesday morning, everyone awoke to much calmer conditions, and it was obvious that people were feeling better since breakfast was well attended. Today, we will be at sea all day again, and hope to get to Elephant Island sometime tomorrow morning. There was a kayak briefing for those of us who want to try kayaking in Antarctica, which we hope to be able to do, but is very weather dependent. Only 50 people want to try this activity, so excursions will be limited to 12-14 that will go at any one-time. The appropriate gear is to wear long underwear covered by a polar fleece jumpsuit and with an outer layer of a neoprene dry-suit. The dry-suit comes with neoprene boots and mittens which hook directly on to the paddle. If we get the chance, we will use 2-man kayaks.

The sailing today is so much calmer but with lots of clouds. It has snowed or rained off and on nearly all day, and the air temperature is dropping – now reading at just a few degrees above freezing. In today’s lectures, we learn of the Chilean rescue part of the Shackleton Story from our Chilean Guide, Marco. After 3 failed attempts to rescue his men from Elephant Island. Shackleton enlisted the aid of the Chilean Navy. The Chilean culture has a long history of rescues, and the Chilean Navy assigned the task to Captain Piloto Pardo, the Captain of the Yelcho, a coal-fired, single hulled ship stationed in Punto Arenas, where he was responsible for resupplying the Navy bases along the Beagle Channel and Chilean fiords. Captain Pardo accepted the task with determination, and, after stopping to take on a load of coal, took Shackleton and his two mates past Cape Horne and sailed slowly through the fog towards the Antarctic Peninsula. After 3-days of avoiding icebergs in the fog, they arrived at Elephant Island, sent a rowboat ashore and, within one hour, were able to rescue all 22 men that were stranded there. They then headed back to Punto Arenas. Piloto Pardo had had no radio or technological equipment on any kind – just determination, perseverance, and the knowledge on how to carefully and skillfully sail through the fog. When he arrived home with the rescued men, he was offered 25,000 pounds sterling from the British Government as a reward. However, he was a humble man and refused the money, stating was only “doing his job”. Today, on Elephant Island the mountain ridge is called Pardo Ridge and a small peninsula is called Cape Yelcho. Here on Elephant Island at the point of the rescue, there is a bust of Pardo in recognition of his service. Yet in Punto Arenas, and in the British stories of Shackleton, there is little recognition of him.

That night, we had a seated dinner in honor of Shackleton with proper “British” food – lamb, potatoes, brown bread, etc. That night we spend a lazy evening, take a dip in the hot tub, and prepare for tomorrow. We should then officially be in Antarctica!